Nicholas Winton Rescued 669 Children From The Holocaust And Kept The Secret For Decades

Guest Contributor

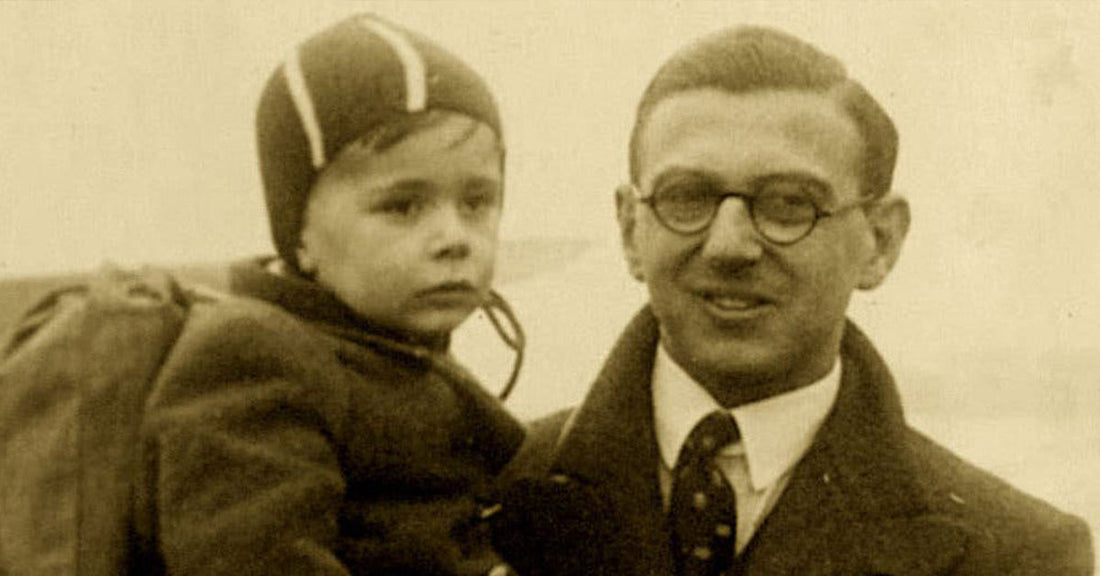

In the shadow of World War II, when the Nazi threat loomed over Europe, one man quietly orchestrated a rescue mission that would save hundreds of lives. Nicholas Winton, later dubbed the “British Schindler,” helped 669 children escape from Czechoslovakia just before the outbreak of the Holocaust. His story, though largely unknown for decades, is a powerful testament to what courage and compassion can achieve in the face of overwhelming darkness. For those interested in Holocaust rescue efforts or stories of moral bravery, Winton’s legacy offers a deeply moving example.

Winton was a London-based stockbroker in 1938 when he received a phone call that would change his life. A friend, Martin Blake, asked him to cancel a planned ski trip and instead come to Prague to help with the growing refugee crisis. Winton agreed on impulse. What he found in Prague shocked him: camps filled with Jewish families displaced by the Nazi annexation of the Sudetenland. Immigration restrictions across Europe meant that most of these families had nowhere to go. Yet Winton saw a narrow window of opportunity—Britain allowed child refugees under certain conditions—and he seized it.

Working with a small group of colleagues, including Trevor Chadwick and Bill Barazetti, Winton set up an office in Prague. There, they met with desperate parents hoping to secure a future for their children. The process was emotionally wrenching. Parents knew that sending their children away might mean never seeing them again. Yet they lined up in the thousands, trusting strangers with their children's lives.

The logistics were daunting. Winton had to arrange train transport out of Nazi-occupied territory, find foster families in Britain, and secure entry visas—often under tight deadlines and bureaucratic resistance. When the British Home Office delayed visa approvals, Winton and his team resorted to forging the documents. He later admitted to this, recognizing that legality often stood in the way of morality during those perilous times.

Between December 1938 and the end of August 1939, eight trains carried children from Prague to London. The ninth train, scheduled for September 1—the very day Germany invaded Poland—was halted. The 250 children aboard were never seen again. Winton later reflected on that moment with sorrow, recalling how hundreds of families waited in vain at Liverpool Street Station. “If the train had been a day earlier, it would have come through,” he said.

The children who made it out owed their survival to Winton’s persistence and ingenuity. Many of them later spoke of their final moments in Prague: the tearful goodbyes, the confusion, and the fear. Some parents hid their emotions to protect their children’s sense of security. One survivor recalled being told he was going on a holiday to visit an uncle in England, unaware that it would be the last time he saw his parents. Another, Zuzana Marešová, remembered the haunting image of parents waving goodbye through the train windows, repeating the hopeful words, “See you soon.”

Despite the scale and impact of his efforts, Winton remained largely silent about his role for nearly 50 years. In fact, when he ran for local office in Maidenhead in 1954, he mentioned the rescue mission in only a single line on his campaign leaflet. It wasn’t until 1988, when his wife Grete Gjelstrup discovered a scrapbook in their attic containing names and photos of the rescued children, that the world began to learn of his actions. She refused to let the story fade into obscurity, insisting, “They are children’s lives.”

The scrapbook eventually reached a Holocaust historian, and soon after, Winton was invited to appear on the BBC program That’s Life. In a now-famous segment, he was reunited with some of the very children he had saved, now adults. The moment was emotional and genuine. Though Winton later expressed discomfort with the surprise nature of the event, wiping away his own tears during the broadcast betrayed the depth of feeling he carried.

In the years that followed, Winton received numerous honors, including membership in the Order of the British Empire and recognition from multiple governments. A planet discovered by Czech astronomers in 1998 was even named after him. Yet he consistently deflected praise, often highlighting the bravery of those who remained in Prague, like Chadwick and Warriner, who faced far greater personal risk. “I wasn’t heroic because I was never in danger,” he told The Guardian in 2014.

Winton passed away in 2015 at the age of 106, on the anniversary of the largest evacuation he had arranged—241 children. His humility remained intact until the end, and his story continues to inspire new generations. I found it striking that such a monumental act of kindness could remain hidden for so long, not out of secrecy, but because the man behind it never sought recognition. His legacy is not only in the lives he saved, but in the quiet, determined way he chose to save them.